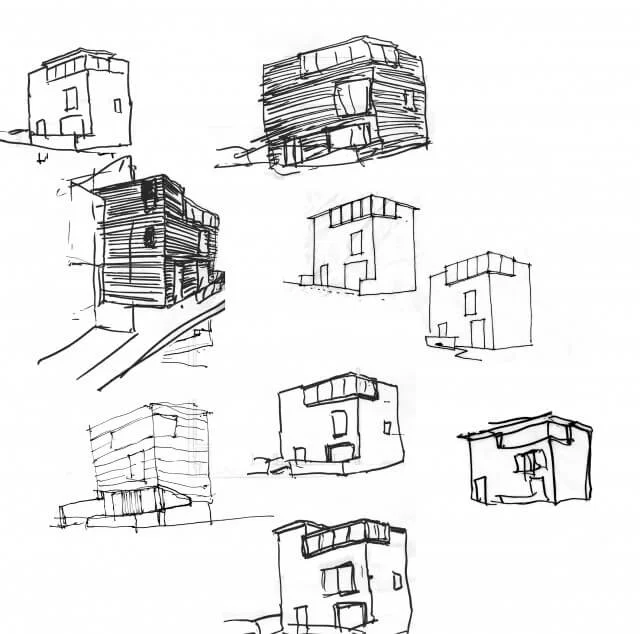

Rather than thinking about what it would look like, a lot of our discussions revolved around the atmosphere of the house and the way different spaces would relate to one another. Emily is an interior designer, so we each had different, but fortunately ...

Precedents I – Newington Green House

Barrington Court

On Sunday we headed over to Barrington Court, the first large house taken on by the National Trust (in 1907), and one that caused them such serious financial difficulties that it was held up for years after as an example of why they should be vary wary of taking on other stately homes. For over ...

The Wild South-West

I’ve been getting rather agitated recently about a planning application submitted for a new house in our village. As new-comers we’ve kept our heads down, particularly as our neighbours have been so generous and welcoming to us and our unconventional house, but this proposal exemplifies a superficially benign type of development, the cumulative effect of which is a creeping erosion of the character of the countryside.

Why Passivhaus?

Cadaques

I spent last week in Cadaques, a coastal town in north-east of Catalunya. I was struck by how well some of the new houses on the outskirts of town have been built into the natural landscape.

Once a sleepy village, Cadaques was made popular as a tourist destination by its seclusion from the crowds on the Costa Brava and associations with artists of the Modern era such as Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dali. Since the 1950s the original whitewashed fishing village has been expanding out of its little bay over the surrounding hillsides. The town is hemmed in by the Cap de Creus national park on one side and the sea on the other so there is immense development pressure on any available parcel of land. Most of the buildings in the old town are painted white but recent new developments on the periphery use the local stone. I don’t know the planning policy but it looks like it has been decided that beyond a certain limit new buildings would have to be clad in stone to preserve the visual clarity of the original nucleus of the town. The policy wasn’t to stop development but rather to impose a kind of school uniform that all the individually designed houses have to wear that gives maintains a sense of place.

The hills behind Cadaques have been terraced with dry stone walls and planted with olive trees for centuries. In many of the new developments stone walls form terraced gardens on the steep slopes and I noticed quite a few where the terraces merge into the walls of houses. The houses are all concrete framed and the stone is just cladding but the homogenous material blurs the distinction between the buildings and the natural forms and colours of the hillside.

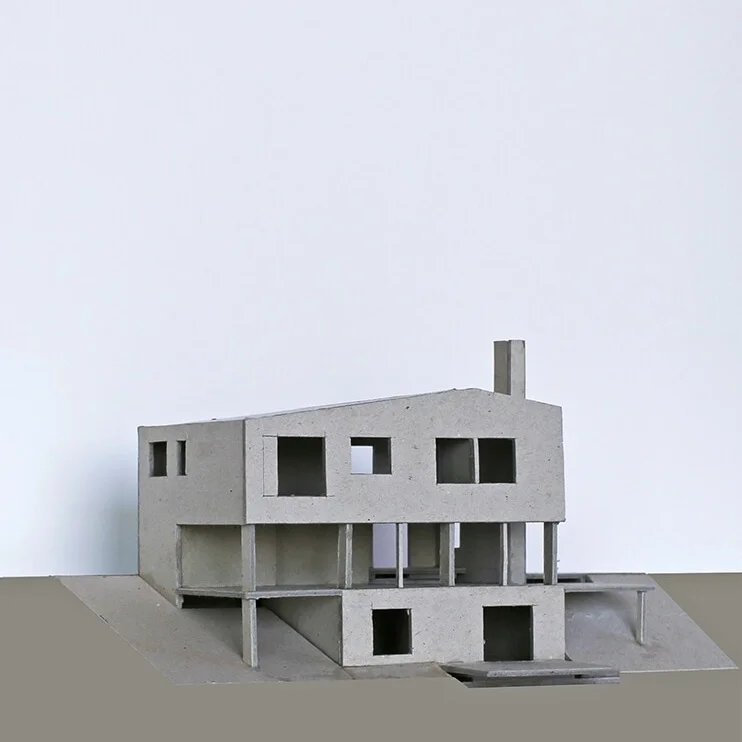

The gardens of the houses around where we stayed were planted with indigenous species, particularly Mediterranean stone pines (pinus pinea) that go some way to absorbing the houses into the landscape. It helps that all new buildings in Catalunya have to be drawn up by an architect so there is plenty of invention within the restrictions. The house below reminded me of our Newington Green House:

MORE POSTS:

Homes for Heroes

Finding the right rural building plot isn’t easy. You (quite rightly) aren’t allowed to build on open countryside outside a village curtilage as defined in the Local Development Framework. Unless you are a major house builder the only options are to divide up a larger plot within a village, to convert an agricultural building or to buy a house and knock it down. The plot we found had a ramshackle bungalow on it whose owner had recently died having lived in it for 40 years. Its location is idyllic, just within sight of the next building at the edge of a village with a fantastic view to the south across the Somerset Levels.

Our intention was always to demolish the bungalow and start again – after all, building a new house was the deal that had lured me out of London. But there was something about the simplicity of the little place, 4 rooms around a central hallway-cum-sitting room, and the fact that someone had lived here happily for so long with a minimum of modern comforts that made us rather sentimental about it. It had no pretentions, just the quiet dignity of something built efficiently and economically to fulfill its purpose.

I don’t have any information on the original design – does anyone out there know more about it? Perhaps it was never intended to last long. There’s no reason a timber frame won’t last for centuries if kept dry but with only a small fireplace to dry out the damp and less than adequate maintenance ours was suffering seriously from rot. A pipe had burst, soaking the inside and by the time we started work there were mushrooms growing on the floor. There was no alternative but to start again. We salvaged what materials we could but most of the timber was rotten and the walls were lined with asbestos boards. All we have are the thin softwood floorboards which so far have only been used to make compost bins.

We had looked at a few sites that had similar bungalows on them, all being sold as building plots, and we’ve found several more not far away. Ours was built around 1920. It had a softwood timber frame with painted softwood cladding and an asbestos shingle roof. After the 1st World War the shortage of labour and orthodox building materials led to the government offering subsidies to local authorities for houses built using non-traditional methods that could take advantage of the spare production capacity from the armaments factories. Systems were developed using concrete, steel, cast iron and timber and around 50000 were built in the decade following the 1st World War.

And now people like us are pulling them down. Maybe its inevitable but it is rather sad that a whole typology is slowly being removed from the landscape. Part of their appeal is their small size and lack of permanence – ours certainly had something of the frontier about it. A flimsy timber system-built house is the antithesis of the Englishman’s house as his castle. We liked the way the well-kept garden had grown around it so that the fruit trees were of a similar scale to the bungalow, preventing it from dominating the site.

Here are a few photos of ours taken in the autumn sunlight the first day we went to see it in 2010. If you want to stay in a similar house there is a 1920s Boulton & Paul bungalow in north Devon you can rent owned by the Landmark Trust.

MORE POSTS:

Metalwork

This morning I went to see the progress on some of the metalwork for our house. I love the fineness of metalwork, the crisp lines and economy of material, and the way it can bear the marks of how it was made. We’re using steel for a number of internal and external elements to provide a contrast with the chunkier oak structure and linings. Two metalworkers are making things for the house as there’s quite a lot of it and everyone seems to be busy despite the recession. These photos were taken atCastle Welding.

Long Sutton Passivhauses

Welcome

Hello, and welcome to our Journal. I am Graham, one half of Prewett Bizley Architects, living in Compton Dundon, a small village in Somerset. I moved here with my wife Emily, an interior designer in 2011 having lived in London for 15 years. We had our son Arlo two weeks after we arrived but he was only one of two major projects that have dominated the first two years. The other was building our own house on a beautiful south-facing slope just above the Somerset levels. We bought the site at auction in 2010 and had obtained planning permission by the time we moved. So my first 8 months in Somerset were spent doing the detailed design for the house, changing nappies, and trying to get some sleep myself occasionally. Work started on site in January 2012 and we moved in at the start of November the same year. The house has been built to Passivhaus standard which means it has extremely high levels of insulation and air-tightness. It wasn’t finished of course but at least we were in and we have been carrying on with the work in a slowly decreasing state of chaos around our day jobs.

In the Journal I will be talking about architecture, low-energy construction, and urban design. Primarily though I want to explore aspects of rural architecture and planning. Being a new arrival in the country I am conscious of bringing with me the attitudes of an urbanite, one of them Londoners. I am keen to explore issues that determine how development occurs outside of urban areas, to develop an approach for how to design in the countryside and to understand better where I am.

Please get in touch or leave a comment. I’d love to hear from you!